Stock Market Crash: Should We Fear It?

Warnings of an impending stock market crash have been increasingly common lately. News reports are abuzz with speculation about a possible recession and a global economic slowdown.

Against this backdrop, the recent actions of legendary investors are also remembered: Warren Buffett reduced his holdings of certain assets before retirement, locking in profits after years of growth.

It's no wonder that private investors are worried: are we on the brink of another collapse?

But is a stock market crash really that scary if you're investing for the long term and are confident you won't need the money you invest for the next 5-10 years?

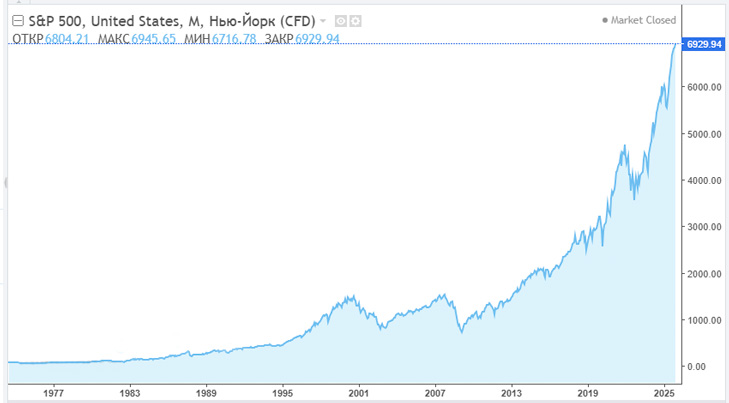

Let's try to understand how the market behaves in practice, taking as a basis one of the most famous and representative stock indexes - the S&P 500 , which reflects the dynamics of the 500 largest US companies.

How the Market Survived Crashes: 60 Years of History

Over the past 60 years, the American market has experienced repeated major upheavals. Each time, it seemed like the "end of the stock market era," but the outcome always turned out differently.

Looking at the key crises in the index's history, the picture is revealing:

| Crash (year) | Cause | Max. drawdown from peak | Recovery time |

| 1973–1974 | Energy shock (OPEC, inflation) | –48% | ≈ 7.5 years (before 1980) |

| 1987 | Black Monday | –33…34% | 1 year 9 months |

| 2000–2002 | The dot-com bubble | –49% | ≈ 7 years 7 months |

| 2007–2009 | Global financial crisis | –56,8% | ≈ 5 years 5 months |

| 2020 | COVID-19 pandemic | –33,9% | ≈ 5 months |

1973–1974 – The oil crisis and stagflation. The index lost almost half its value. Recovery took about seven years, but the market didn't just return to its previous levels – it laid the foundation for further growth for decades to come.

1987 – "Black Monday ." A one-day drop of more than 20% seemed catastrophic. However, less than two years later, the index had completely recovered its losses.

2000–2002 – The dot-com crash. The tech bubble led to a decline of almost 50%. The recovery was long – about seven years, but it was after this that the market entered one of its most powerful growth cycles.

2008–2009 – The global financial crisis. The most painful crash since the Great Depression: minus 56%. Nevertheless, about five years later, the index reached new all-time highs.

2020 – the COVID-19 pandemic. A decline of more than 30% occurred in just a few weeks. And this is perhaps the most striking example: the market recovered in less than six months.

The key takeaway from the S&P 500 story

History shows a clear pattern: the market has always recovered after crashes. Yes, recovery times have varied—from a few months to seven years. But what's fundamentally important is that no major crisis has ever marked the "end of the stock market.".

Looking at the bigger picture, the numbers speak for themselves:

- Over the past 60 years, the value of the S&P 500 has increased approximately 77-fold;

- over the past 10 years – approximately 4.6 times, despite the pandemic, crises and geopolitical instability.

This is why, for a long-term investor, short-term crashes are not a disaster, but part of the market cycle.

Why Falls Aren't as Scary as They Seem

It's important to remember another fundamental point. A stock's price is merely a reflection of market expectations. Businesses, however, continue to operate and make money even during crises.

Companies included in the index in most cases:

- continue to make a profit,

- pay dividends ,

- adapt to new economic conditions.

Profit, not the current stock market price, is the fundamental basis of a business's value. As long as companies are making money, the market has a basis for recovery.

If you're investing for the long term and don't plan to withdraw your money within the next 5-10 years, there's no need to fear a stock market crash. The history of the S&P 500 clearly shows:

After each collapse, the market went through a recovery phase and then moved on to new growth.

Short-term declines are the price an investor pays for long-term capital growth. For a patient investor, they often become an opportunity rather than a threat